Some basic facts bear repeating. The gap between rich and poor in the UK was at its narrowest in the 1970s, a decade when trade unionism was at its strongest. In 2018 there is an obscene gap between those flaunting great wealth and working people battered by austerity and privatisation. We have the prospect of millions of people working in low-wage or zero-hour contract conditions.

The word ‘gig’, once used by jazz musicians when they were hired for a performance, has now been appropriated to describe an aspect of working life. It all sounds very hip or cool but the reality is that there is now a permanent class of people who are subject to the whims of their employers. The sheer uncertainty of the number of hours people will work from day-to-day creates massive financial instability in their lives.

How did we get to this dire situation? One answer is that a succession of Tory governments in the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher tore up laws giving unions powers to protect fellow trade unionists and replaced them with repressive trade union legislation which allowed the government to sequestrate union funds, limit trade union solidarity and restrict the numbers of trade unionists picketing at any one time.

Thatcher and a group of Tories around her were contemptuous of trade unions and were prepared to use the powers of the state to destroy them. One group of workers was a particular target – the miners. Thatcher prepared meticulously for what she saw as a crucial test of her power. Indeed in 1981, when she had not had time to prepare for a miners’ strike, she retreated and conceded to miners’ demands.

But by 1984 coal stocks were high, the police had been trained in aggressive riot control techniques, and, after an election victory buoyed up by the Falklands War in 1983, she was ready for a confrontation with the miners. The strike began in March 1984 when the National Coal Board announced the closure of Cortonwood Colliery, near Barnsley. It was a body blow to the Yorkshire miners because the pit had just had millions of pounds spent on it and miners from another pit which had just closed transferred to it.

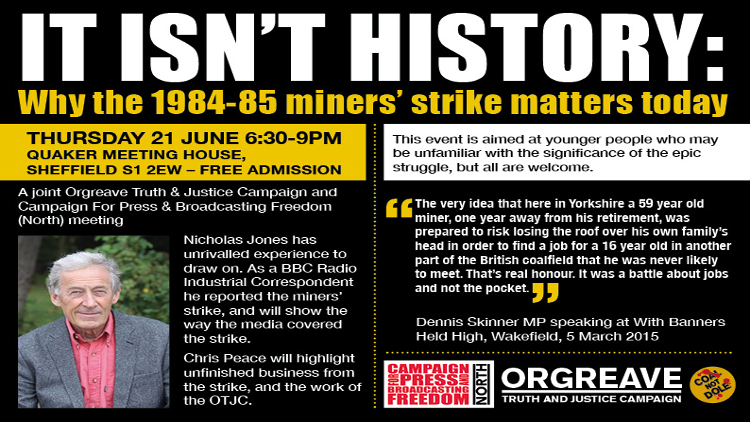

The closure was the trigger for a national strike by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). It was not a strike about pay but about protecting jobs and communities against a devastating round of pit closures. Dennis Skinner, the veteran Labour MP from the former mining community of Bolsover, and himself a former miner, put it well when he spoke at ‘With Banners Held High’ in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, on 5 March 2015 – the 30th anniversary of the return-to-work by the miners after the year-long strike. “The very idea that here in Yorkshire a 59 year old miner, one year away from his retirement, was prepared to risk losing the roof over his own family’s head in order to find a job for a 16 year old in another part of the British coalfield that he was never likely to meet. That’s real honour. It was a battle about jobs and not the pocket,” he said.

18 June 2018 will mark the 34th anniversary of a pivotal event in the year-long miners’ strike – the Battle of Orgreave. On that day the NUM deployed 5,000 pickets from across the UK to prevent access to the Orgreave coking works by strike-breaking lorries that collected coke for use at the British Steel Corporation mill in Scunthorpe. It was a bright summer day, with many miners dressed in jeans, T-shirts and plimsoles, and in a relaxed mood. Against them were deployed around 6,000 officers from 18 different forces, equipped with riot gear and supported by police dogs and 42 mounted police officers.

What followed that day was a brutal confrontation by the police with the pickets. Apart from the assaults by mounted police, short-shield units indiscriminately attacked miners. 71 pickets were charged with riot and 24 with violent disorder. However, both the police and most media coverage placed the blame for the carnage that day on violent picketing by miners.

Establishing the truth about who was responsible for organising the police assault has become the focus of the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign (OTJC), a tenacious group which includes striking miners who were arrested and charged at Orgreave. The OTJC was set up in November 2012, after the Hillsborough Disaster report revealed that South Yorkshire Police had fabricated evidence about their role in the disaster. A brilliant BBC ‘Inside Out’ programme which exposed the same role by South Yorkshire Police’s use of fabricated evidence against miners arrested at Orgreave also provided another spur.

The OTJC wants a full public inquiry into who planned, organised and authorised the police assaults that day. On Saturday 16 June 2018 it will organise a march and rally near to the Orgreave site to keep its work in public focus. The following week in Sheffield, on Thursday 21 June, there is a public meeting It Isn’t History: Why The Miners’ Strike Matters Today with Chris Peace from the OTJC and Nick Jones, the former BBC journalist who covered the miners’ strike for BBC Radio. (Full details of all OTJC events can be found at www.otjc.org.uk)

The defeat of the miners and their return to work on 5 March 1985 had enormous repercussions, with Thatcher embarking on widespread privatisation of public utilities. James Bloodworth’s Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-Wage Britain, published in March 2018 on the thirty-fourth anniversary of the start of the year-long miners’ strike, reveals other grim consequences. The author spent six months living as a zero-hour worker.

The first job Bloodworth took in 2016 was at the Amazon ‘fulfilment centre’ in Rugeley, Staffs. In the early days of the 1972 miners’ strike as a journalist I went to Lea Hall Colliery in Rugeley to meet striking miners. It was a prosperous town with, as well as the pit, two power stations, and Armitage Shanks, Thorn Automation and Celcon factories. Lea Hall Colliery opened in 1960 and closed in January 1991 throwing 1,250 men out of work. Now the biggest employers in Rugeley are Amazon and Tesco.

Amazon came to the town in 2011. The firm’s vast warehouse, the size of ten football pitches, contains four floors. Bloodworth’s job was a ‘picker’ which involved rushing up and down the long, narrow aisles selecting items from the two-metre high shelves and putting them in big yellow plastic boxes called ‘totes’. These were wheeled around on blue metal trolleys before being sent down conveyor belts to be packed for delivery. On an average day he was expected to send around 40 totes down the conveyor belts. As he rushed around he carried a hand-held device which tracked his every movement. For every dozen or so workers a line manager would be monitoring their work rate through the devices.

In this highly-pressured environment with slogans and photographs plastered on the walls (‘We love coming to work and miss it when we’re not here’) you were designated as an ‘associate’ not a worker and if your performance fell below the company’s targets you were not sacked but ‘released’.

What happened in Rugeley can be replicated in former mining areas around the country. Sports Direct’s biggest warehouse, which has been compared to a ‘workhouse’ and a ‘gulag’ by Unite, is located in Shirebrook, Derbyshire, the site of Shirebrook Colliery which closed in 1993. ASOS, the mail order company run by the global logistics giant XPO, is located near the former mining community of Grimethorpe in South Yorkshire. The GMB union highlighted the ‘invasive monitoring and surveillance’ at the firm with agency workers and permanent staff saddled with onerous targets to process high volumes of orders each hour, and being discouraged from stopping to drink water or use the toilet.

A common feature of all these companies offering precarious, low-paid work is a fierce resistance to trade union organisation. It is only through undercover work by reporters and writers like James Bloodworth, and the work of unions like Unite and the GMB, that we have found out what goes on inside these anonymous warehouse structures.

A TUC report in 2017 estimated that one in ten UK workers – three million – now work in insecure jobs. This situation has come about as a direct result of the assault on trade unions under Thatcher, and the wave of de-industrialisation she unleashed. High-paid, full time jobs with pensions and holidays with pay disappeared. And, of course, the values which the miners fought for in 1984-85 – jobs and the defence of communities – meant nothing to a prime minister who thought that ‘there is no such thing as society’.

———————-

Granville Williams is a journalist and author. His most recent book is The Flame Still Burns: The Creative Power of Coal. He is on the National Council of the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom.

Leave a Reply