by James Curran

Seething union activists at a Nottingham conference in 1979 demanded to know from press workers what they were going to do about press lies and distortions. I was at the conference as a stray media historian, and joined the huddle of people from the press. We decided – rather defensively – to set up a reform group.

We called it the Campaign for Press Freedom (CPF). (Broadcasting was not inserted into the title until 1982). The founding committee produced with surprisingly little difficulty an eloquent founding document, Towards Press Freedom (.pdf).

Sponsors were approached including not only trade union general secretaries but establishment figures like bishops, senior lawyers and top politicians (later supplemented by actors), nearly all of whom said yes. Money initially came from the press unions. CPF was first lodged at the print union SOGAT, before moving into an office in central London funded by Rowntree.

Because CPF began as a union creation, it was first launched at the 1979 TUC Congress. Its London launch later that year was attended by over 400 people, and Towards Press Freedom quickly sold out. It was clear that we had the wind behind us.

CPF’s first initiative was to launch an industrial right of reply campaign. A small group – consisting of two very impressive print union officials (George Jerrom and Julian Mitchell), an NUJ activist (Anna Coote) and myself – was established to carry the project forward.

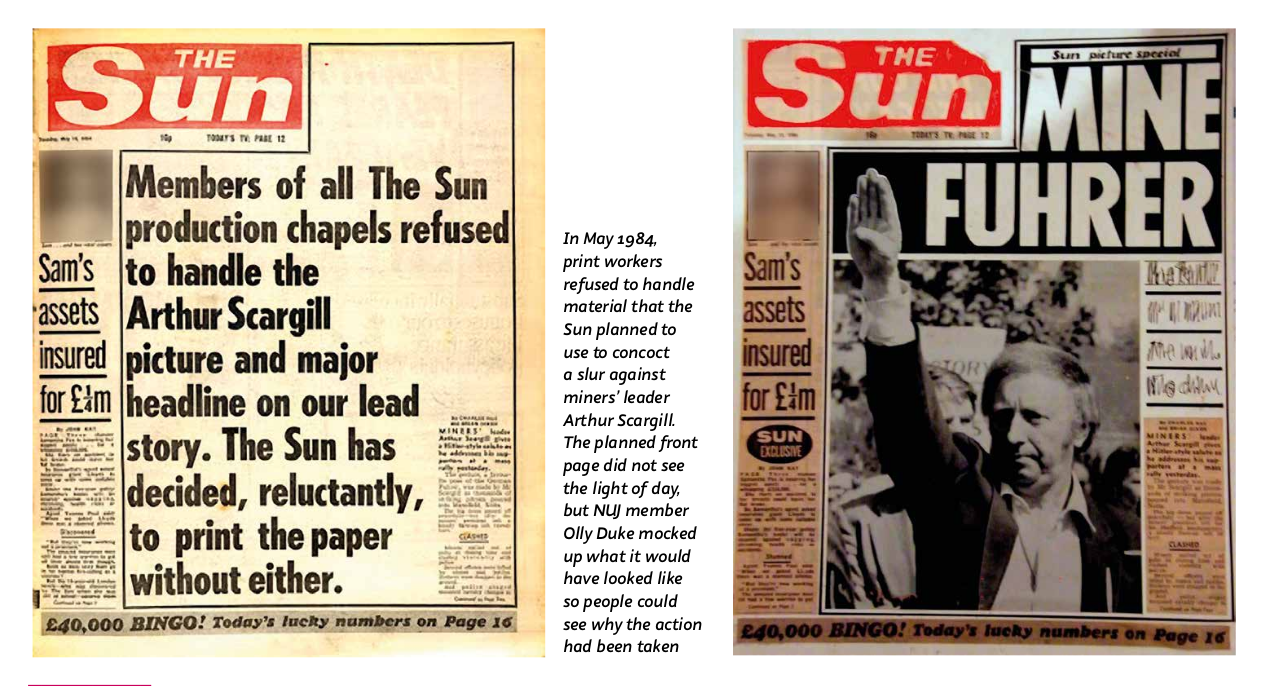

We wrote a pamphlet arguing that press freedom was not a property right possessed by owners but belonged to all, urging press workers to secure the right of reply for victims of press distortion. We then co-opted print union shop stewards, including one with the awesome title “Imperial Father of the Chapel” at the Daily Mail (Mike Power) who turned out to be awesomely effective.

The right of reply to mendacious anti-union and racist articles was secured through the threat of industrial action in a number of papers including the Daily Mail, Daily Express, Sun and Observer (although the News of the World astutely published a blank space rather than permit a reply).

The press response was to cry censorship, and declare that an alternative means of redress was available through the Press Council. Anticipating this, we had set up an inquiry into the Press Council chaired by the lawyer Geoffrey Robinson, who produced a devastating indictment of the Press Council’s limitations in a book called People Against the Press (1983).

By 1986, CPBF (as it was now called) had 472 trade union and Labour party organisations affiliated to it. With their help, CPBF’s proposals for supporting minority papers, part-funding new papers and introducing stronger anti-monopoly controls were adopted by both the TUC Congress and Labour Party Conference. These Nordic style measures became part of the official Labour Party programme.

However, the strength of CPBF – its strong union base – was perhaps also its weakness. An attempt was made to build closer links to new social movements and universities. This aspiration was embodied in Bending Reality (1986), a CPBF/Pluto activist book, with contributions from feminist, anti-racist and Gay Liberation campaigners and academics like Stuart Hall, as well as from trade union activists. But, apart from affiliates, CPBF had in 1986 only 932 individual members.

The breaking of the press print unions in the mid-1980s, and the refusal of New Labour governments (1997-2010) to contemplate radical media reform for fear of upsetting media proprietors, could have undone CPBF. But CPBF, with strong broadcasting staff support, came to the aid of public service broadcasting when it was threatened in the 1980s. CPBF activist Tom O’Malley spearheaded an effective parliamentary lobby, with cross-party support, for a legal right of reply in the 1980s and 1990s, and co-wrote a fine book, Regulating the Press (2000).

CPBF fought for media reform for almost 40 years. It published Free Press, a high quality publication, for most of this time. It was a pioneer – and has spawned other organisations, such as the Media Reform Coalition, that will fill the space it has vacated.

James Curran, Professor of Communications at Goldmiths, played a key role in the formation of the CPBF. He is the author (with Jean Seaton) of Power Without Responsibility: The Press, Broadcasting and New Media in Britain, now in its eighth edition.

This article was first published in CPBF’s journal Free Press No 216.

Leave a Reply